I read a beautiful blog post last week from Sara at Classically Homeschooling that really got me thinking. Sara is a classical educator (as is my family) and was writing about homeschooling ‘non academic’ kids with the classical method. The classical model is known for being rigorous. Twelve year olds are studying Latin, learning to write persuasive essays, and (in our Classical Conversations group) drawing the entire world by heart by the end of the year. For the less academic scholar (and their parents), this can be intimidating.

What does it mean to be ‘non-academic’? I don’t think anyone is really non-academic. My kids do academic things everyday. I prefer the term ‘less-academic’ for the purposes of this post.

From my perspective, as the mother of 7 kids with learning challenges like dyslexia, dysgraphia, and ADHD, this means that traditional academic pursuits that require extensive reading and writing are more difficult and require more work than their more academic peers.

Not just this, but their strongest gifts and talents may lie elsewhere – perhaps in the arts, business, or sports.

Sara’s blog post really got me thinking. What does all of this mean for our kids’ education? Should we expect less of them? Should we avoid more difficult subjects? What do we do when they are unable to keep up and master every subject – whether or not they study using the classical method.

Homeschooling the Less Academic Child

Does a child need to be ‘academic’ to succeed in school? If not, what does that look like?

Things move more slowly. One of the hallmark signs of child with a learning disability is the discrepancy between their IQ and their academic performance. They have the intellectual ability but processing, memory, and attention weaknesses make learning more time consuming. The most affective accommodation for students with learning disabilities is more time. Our kids can master any subject – in time.

They don’t need to get an ‘A’ in every subject. I attended a lecture at the International Dyslexia Association conference a few years ago where a young dyslexic woman shared how she managed her learning struggles in college. I loved her candor about choosing the courses that were the most important to her, and focusing on getting ‘A’s in those classes. My dyslexic kids can be near the head of their class in some subjects and near the bottom in others – and that is okay.

An atmosphere of possibilities in your home. This time of year finds many families reassessing their homeschooling options. Some are heading off to private or charter schools. Many are changing curriculum. How are you handling the challenges in your homeschool? One thing homeschooling kids with dyslexia for 20 years has taught me is that they. can. learn. anything. They may not learn it in the same time frame or with the same methods as other kids, but they can. In our home, we face obstacles in learning with the attitude of working together to find a solution or strategy. This is where teaching kids about the power of a growth mindset is invaluable. I teach our kids to say, “I can’t do this – yet.” and not to be defined by the struggle, rather by the overcoming of the struggle.

Focus on learning how to learn. This is perhaps the main benefit of homeschooling kids who learn differently. One kid needs quiet to study, another needs music playing in the background in order to focus. One kid needs to hear information to make it stick and another needs to see it or touch it. Teaching our kids how they learn and giving them the tools and time to practice is giving them a skill that will help them be lifetime learners. Are they learning how to think, to communicate, to be an active part of their education? If they are, then whether they memorize all of their vocabulary words or master their times tables doesn’t matter.

Focus on character. Educating our kids at home involves more than academics. Character traits like perseverance, kindness, and selflessness are becoming less and less common in our youth. Kids who struggle have more of an opportunity to grow in character traits like patience, perseverance, and humility than other kids and that doesn’t need to be a bad thing.

While there are many areas of our kids’ education that can feel out of our control (will they ever master their times tables?), these five areas are things we can control. We can control our pace, our expectations, our attitudes that affect the atmosphere of our homes. We can control what we teach and how we teach so that our kids grow into their God-given gifts and talents.

Keeping Up

What do we do when our kids can’t keep up with their classmates? In non-classroom situations, I teach them at their pace. If they’re reading at a 1st grade level in 4th grade, I teach at that level until they master the content.

What if they’re in a classroom situation? Our Classical Conversations leaders encourage scaling back if necessary. If a child is struggling to keep up, the parent is free to scale back the requirements. They are still working for the same amount of time but perhaps declining every other sentence in Latin or answering questions about literature orally instead of writing them down.

Curriculum is a tool for teaching, not a master to be obeyed.

What about grades?

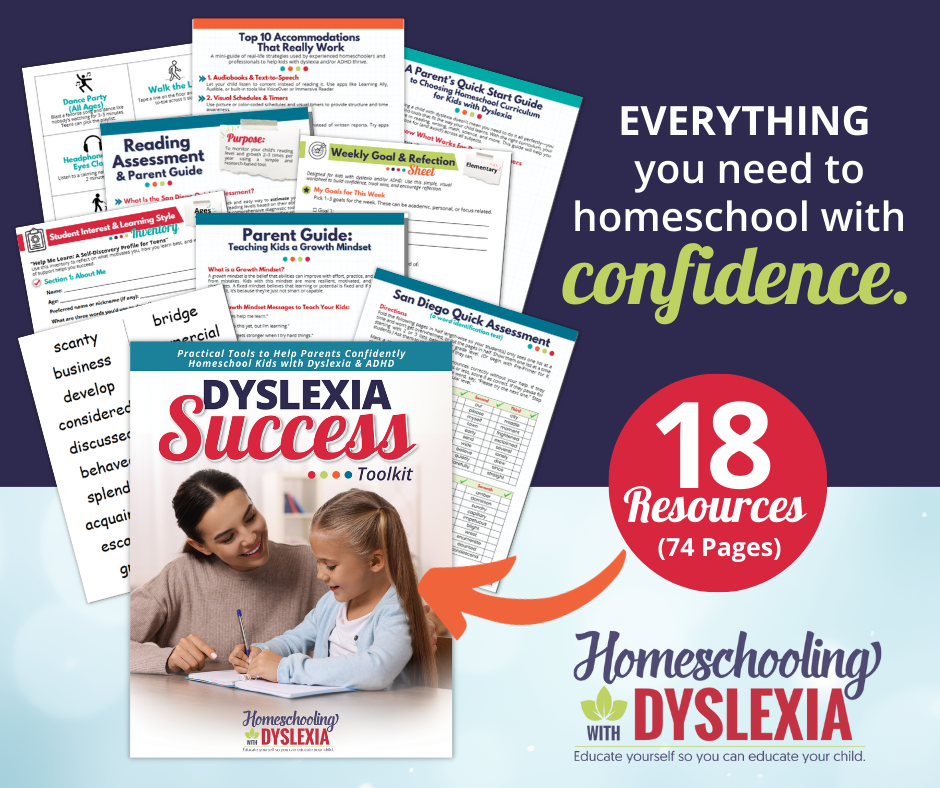

As our children’s teachers, we have the freedom to assign and expect what we know our kids can do. I created an editable grading rubric that I use to set up customized expectations for my unique kids. It’s easy to set up and simplifies assigning a grade based on the individualized goals that we have for our kids/students.

As Sarah beautifully writes in her post (you can read that post here), the goal of education is “to encourage kids to learn, to shape their body, minds, and souls. And to help children see the beauty of the world.”

How about you? Does a child need to be ‘academic’ to be a success in school?

While my daughter does not have dyslexia, she does have ADHD, as do I, and I homeschool her because she does not learn the way children are taught in public school. She is very visual, with a healthy dose of kinesthetic needs, and her learning needs almost exactly mirror mine. Your article touched on a key focus of mine…teach children to learn.

I do not have my daughter memorize, I work for understanding. For instance, I am 50 years old and still cannot remember the dates of the Civil War; however, I understand it, I know that it occurred during the mid1800’s, and I can discuss it in depth, even down to military tactics used. Can I tell you the names of prominent figures from that time period? Only about three, but I know where to go should I want to retrieve that information.

I am teaching her to learn, to discern what is important and what really is not, and to use tools to help her learn.

I refer to your blog often, not only for ideas for my own daughter, but for ideas for students I work with on an intervention basis. I appreciate the time you take to share.

I’m with you on that Amy. Stepping back from the teach and test method of education gives us the freedom to educate our whole, unique child. 🙂

I really think the term ‘academic’ or ‘non-academic’ to describe anyone is too much of a label that could lead to deficit or false thinking about individuals with disabilities. What does it mean to be academic? A person can read strictly through ‘auditory reading’–in the case of someone who has profound difficulties with reading, but still be highly ‘academic’ in terms of having a great wealth of experience and/or knowledge in certain areas.

I would also challenge the use of IQ in determining whether someone has dyslexia or not, for similar reasons. Some people with low IQ who struggle with reading may also have dyslexia and others who have very high IQ and perform well in reading, may still have characteristics of dyslexia–they’ve learned to cope very well. Sometimes people use this diagnosis criteria and it can be a comfort to think my child may have dyslexia but at least they’re smart, but the truth is smart is a choice. IQ is a myth. (Google all the criticisms of IQ tests.) Some of the people who claim the highest IQ’s, say the dumbest things (see Trump’s twitter feed).

Bottom line is, thinking of someone as academic or not academic is too essentialist–it tries to put people in categories that don’t exist, and unfortunately, those with disabilities too frequently get dubbed ‘non-academic.’ So, no, I don’t think the term is helpful.

That is also why I love what you are saying about the mindset that focuses on growth and agency!

I tend to agree with you about any label being limiting. There are kids with learning issues that excel in school. That is why I first set out to define what ‘academic’ really means. There are kids who overcome huge obstacles daily to excel in school. There are others whose path isn’t one of higher education. And that is okay. We were all created for purpose and we can’t all be lawyers! I agree with your thoughts on IQ as well. Studies have shown that it is less IQ and more strength of working memory that determine academic success. Many kids with dyslexia etc have weak working memory skills which makes learning more difficult than for kids with strong working memory. And then you have the effect of a person’s grit or determination. Grit is a better indicator of academic success in college than IQ or SAT/ACT. One theory of education that fascinates me is that of Multiple Intelligences</strong> that theorizes that there are many kinds of intelligence and that word and logic smarts (the school smarts) are just two ways to manifest intelligence. My hope for this post was to ponder the idea of what education is – especially for kids who struggle with it.

Thanks for this look into dyslexia. I like the focus on character. My dad always used to say, ‘So long as you follow the Lord, I don’t care about the rest.’